A Wine Tutorial

for the Curious

really want to know about wine

The wine cup is the little silver well,

Where truth, if truth there be, doth dwell.

(William Shakespeare 1564–1616 CE;

As You Like It, 1599 CE)

After wine blurts truthful speech

(Chinese saying)

In wine, there is truth

In vino veritas

(Pliny the Elder: 23–79 CE)

In the Beginning

Alcoholic beverages have been around for 10,000 years or more.

A

feast is made for laughter, and

wine maketh merry, but

money answereth all things.

(King James Bible: "Ecclesiastes" 10.19)

An Enduring

Beverage

The ancient Greeks described wine as "

Fermentation

The

A bottle of fine wine can be ruined when stored in a warm location. Storage temperatures below

Both

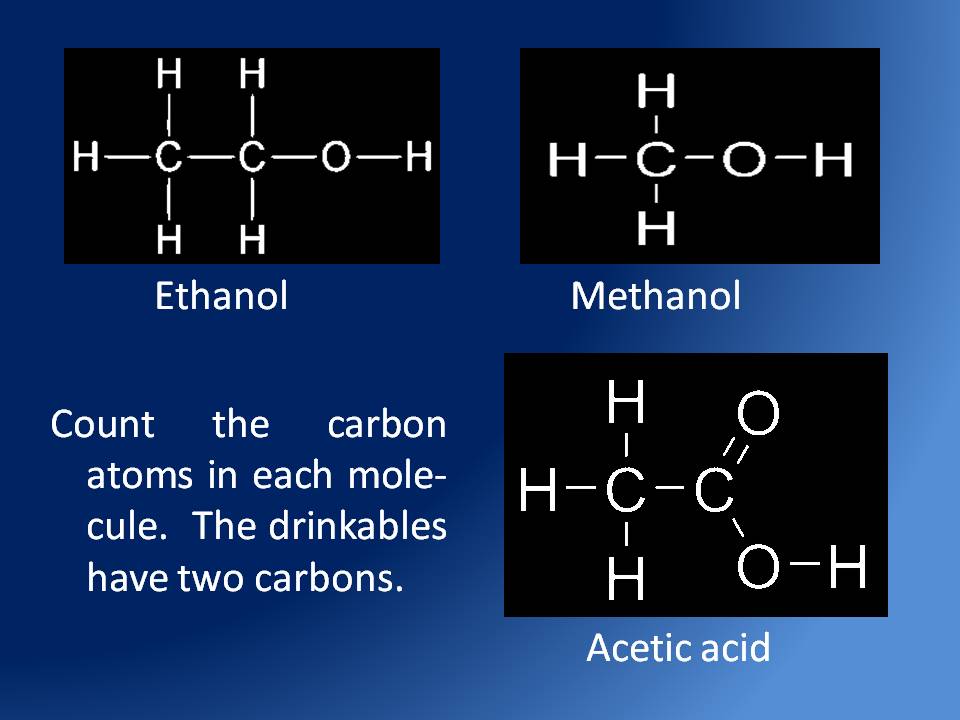

Ethyl alcohol (

Making Wine

If you store for a week or two at room temperature a capped bottle of freshly extracted sweet juice from almost any fruit, a bottle of vinegar would probably be the result. Whether the juice turns to wine or turns to vinegar depends on a series of factors, for example:

Wine can also be made from pure honey or with spices and honey diluted with water, a beverage known as

Selecting Wine

When entering a wine shop, one may become utterly overwhelmed by the large variety of available choices, the bewildering array of alluring bottle labels, and a huge range of prices. How can some order be put into all of this bewilderment?

First, let us assume that we are talking about grape wines. Non-grape wines are another story for another day. Although 8,000 or more varieties of grapes exist, only a relative few varieties are grown for making wine. Disorder can be brought to order by classifying wines according to a hierarchy of characteristics; let us start with color:

The longer the maceration period, the more

So,

a few days or more forwhite several weeks or more forred an intermediate length of time forrosé

The first few days or more of maceration in the presence of air encourages the multiplication of the yeast, referred to as "

During secondary fermentation, a witch's brew of naturally occurring chemicals interact to form new compounds, which all together affect several prominent characteristics of fine wines.

Other information commonly found on labels is the

Quality-wine labels will often display the

- Cabernet Sauvignon (70%)

- Cabernet Franc

- Malbec

- Merlot

- Petite Verdot

In many cases, quality wines will also display the

Some vintage wines age well, while others do not age well and must be drunk when still

All of this labeling furor arose from several factors at play.

Although the ill effects of US Prohibition and two world wars have had time to heal, much of the world's production of sparkling wines had drifted to California. The gap in European production of Champagne led to the legal loophole that permits California winemakers to use the name "

Characteristics of

Fine Wine

If the foregoing remarks sound a bit prejudicial in favor of red wines, then many

To fully enjoy a complex wine, one might take a sip of wine and swish it around inside the mouth. Different flavors and different sensations begin to reveal themselves as a swirling sip begins to warm from body heat. An intricately complex fine wine presents the wine lover with a richness of tastes and textures that some people may claim are unique to drinking wine. At wine's best, matching different kinds of food with different kinds of

Components of

Complexity and Balance

When eating very spicy hot food, an alcoholic beverage can mellow the intensity of the oil-based "

A complex interplay of these acids affects the character of wine. Some wineries and distributors post the acidity (

Tartaric acid adds to a wine's tartness and is a preservative that suppresses the growth of bacteria that can spoil aging wine.

Malic acid is found in many fruits and vegetables and in wines, adds balance between sweetness and tartness; malic acid plays a role in vine absorption of soil minerals, which can explain a "metallic " palate in some very fine white wines.

Citric acid imparts a sour taste to wine and is used to help stabilize the acidity of many different beverages. Within living cells, citric acid participates in producing energy. Citric acid as a chemical is used in making cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and detergents.

Acidity is measured in units of "

Bear in mind that judging wine by color alone can be tenuous, because a well-aged, high-tannin red wine may have a tannish-colored ring around the edge of wine that touches the glass (the

The greenish or golden hue of a white wine or the color intensity of a red wine are also elements in the enjoyment of fine wine. The spectrum of wine colors ranges from nearly clear to intensely dark red, to purple, or to reddish maroon, depending upon how long the must was macerated and how long the filtered juice after maceration was aged, as well as the type of container, i.e. wooden cask or stainless-steel tank, used for fermentation and for aging.

Older white wines are usually darker in color than younger white wines. Young red wines tend to have a clear color tint, much like colored water, while well-aged red wines tend to be tinged with a brownish or tannish hue, which often indicates mellow tannins. Also, well-aged red wine tends toward an opaque appearance, rather than a translucent or watery appearance.

Enjoy the full experience of drinking fine wines by

- The

tip of the tongue identifiesdry versussweet .- The

sides of the tongue respond toacidity , which is perceived as a tart taste.- The

center of the tongue responds totannins , which induce a dry, lip-puckering, sensation.

Fine wines tend to have a more rich and robust

Grape Varieties

Though 8,000 or so different grape varieties grow around the world, a relatively small number of grape varieties have attained stature in the global wine-drinking community. The broadest category for characterizing wines is by

Cabernet Sauvignon (a hybrid of Cabernet Blanc and Cabernet Franc) originated in Bordeaux, France and is often described as"bold", or "full-bodied", meaning . The "high acidity andrich in tannins Cabernet " family of grapes is among the world's most popular wine grapes. Connoisseurs may argue that Cabernet Savignon produces the world's best wines.

Merlot is a black grape genetically related to Sauvignon that hassoft tannins while maintaining intensity . Winemakers often blend Merlot with other reds to add complexity. Merlot, however, can stand on its own as avarietal (non-blended) red wine

Zinfandel is prominent in Germany and in the United States and is also known asPrimitivo in Italy. Zinfandel is a versatile grape; it can produce arange of wines from whites to dark reds . California Zinfandelrosé has become popular in modern times.

Tempranillo (Spain) is a black grape variety that makesfull-bodied red wines having asoft finish . Red-wine beginners often favor Tempranillo, because of its gentle but full-bodied characteristics.

Nebbiolo (Piedmont, Italy) is among Italy's, if not the world's, most renowned grapes. Nebbiolo produces several very pricey red wines while also being available in more modest choices. At its best, Nebbiolo requires at least several years of aging. Also worth noting is that the color of Nebbiolo is a lighter shade of ruby than other red wines.

The Nebbiolo family of wines is known for itstannic intensity, high acidity, and rich complexity . Above all other considerations, thepowdery limestone soil of Piedmont is what makes these wines so special.

Grenache is grown all over the world and is often blended with Tempranillo and other wines toadd .fruitiness to a blend

Malbec is grown in cooler climates. Malbec enjoys popularity in South America and is afavored pairing with meats , which may account for Malbec being the most popular varietal in Argentina, a country noted for its grass-fed cattle and tasty beef.

Syrah [ originated in ancient Persia (modern-day Iran). Syrah produces ashrah ] (Shiraz or Sirah):full-bodied wine, being spicy and having intense flavors . Iran has not been producing any wine for several decades because of religious prohibitions against alcoholic beverages; however, Syrah grapes are grown across the globe.

Pinot Noir is among the most popular of the popular and is grown in North America, South America, Europe, Oceania, and South Africa. Alcoholic content is about 12 percent, which is a little lower than one would expect in a fine red. Although difficult to cultivate, Pinot Noire is often cited for producing amedium-bodied wine of exceptional complexity after aging. Pinot Noir is also highlyfavored for making sparkling wines and Champagnes .

Riesling is the third most globally popular white wine, though often associated with Germany. Among white wines, Riesling tends to behigher in acid andlower in alcohol than other whites.Because of Riesling's acidity, Riesling wines tend to age well , which is a little unusual for white wines. Riesling is also popular for making "ice wine ", which is a very sweet wine made from frozen grapes.

Pinot Grigio is among the more popular varietals from Italy. These grapes produce a wine that is typicallylighter bodied and crisp ( . In contrast,high acidity ) with ample complexityAlsace (France) Pinot Gris wines are more full-bodied, spicier, and more viscous in texture. They also tend to have greater ageing potential than Italian Pinot Grigio.

Muscat Blanc typically producessweet wines having low alcohol content ( , which is one reason why Muscat Blanc (or Moscato) is a popular5–7% )aperitif . Among the 200 or so variations in the Muscat family, some are slightly fizzy (bubbles), or "frizzante ". Because Muscat grapes grow all over the world, we can guess that this varietal is among the oldest wine-producing grapes. Muscat grapes are alsoused to make raisons (dried grapes).

Chardonnay originated in Burgundy, France, but now grows all over the world. Because Chardonnay favors limestone soils, one can expect local soil characteristics to be expressed in the character of local versions of Chardonnay. The grape'shigh acidity adds . Chardonnay is acrispness to this light-bodied winepopular component of Champagne .

Terroir, the Land

Grapes of a variety that are grown in one vineyard can produce very different wine from the same grape variety grown at another vineyard. Many local factors affect the quality of macerated grape juice and, eventually, the quality of the final wine:

- Chemical composition of the soil

- Drainage characteristics of the soil

- Amount of rainfall

- Prevailing level of humidity

- Amount of sunlight

- Temperature variations

- Length of the growing season

The all-inclusive word for these environmental conditions is "

Grapes that grow in the hot sunny regions of southern California will produce a set of wine characteristics that is distinctly different than the same grape variety grown in the cool sunny mountain regions of Chile and Argentina. These differences are often sufficiently noticeable to novices, as well as to experienced wine drinkers.

Grape-Growing Regions

Several grape-growing regions of the world have achieved a reputation for producing high-quality wines. Soil and climate have a profound effect on the quality and character of the final wine. Grapes of the same type grown in different places can acquire very different character.

Beaujolais region: Abouriou , a close cousin ofGamay Noir grapes, are grown in the Beaujolais region and tend to produce a verylight-bodied red wine , accompanied by relatively high levels of acidity. Notice the light color of the soil.France : the regions ofBeaujolais ,Burgundy ,Bordeaux , andChampagne , as well asThe Rhône Valley .Chablis is asub-region of France's Burgundy region where the only grape variety permitted to be grown isChardonnay . Chablis Chardonnay has a distinctive taste often described as "flinty". The flinty taste derives from the mineral composition of the soil.

Italy : the regions ofTuscany andPiedmont are well-known for their red wines. Some interesting red wines are available from the Italian island of Sicily that has patches of unique soil.

California (USA) :Senoma County andNapa Valley . California wineries have a reputation for consistency in their wine quality, which may have much to do with long periods of consistently favorable weather patterns.

Spain : although much of the Iberian Peninsula is arid, the regions ofRioja andRibera del Duero are well-established producers. The most planted grape in Spain is "Tempranillo ", which has a long history dating back to thePhoenicians (modernLebanon ), who opened the Spanish seaport of Cádiz around 1,100 CE. Despite its arid terroir, Spain is the world's third largest producer of wine.

Hills and valleys along Germany's Mosel River, which flows into the Rhine River. Germany . German wine production is synonymous with two grape varieties: red Spätburgunder, otherwise known as Pinot Noir, and white Riesling, which accounts for two-thirds of total German production. Spätburgunder thrives in warm, but not hot, climates and does well on chalky soil (i.e. calcium carbonate, CaCO3 ).German Pino Noir, therefore, has a distinctive bouquet .Riesling is particularly responsive to the local terroir. Germany's best wines come from the Rheingau, Nahe, Ahr, and Pfalz (or Palatinate) regions. These regions are quite hilly, where grapes are grown on terraced slopes.Terroir is what defines the uniqueness of German Riesling.

The unique soil in much of Oceania is notable for making unique white wines. As one advertisement says, "The secret ingredient is dirt."

Oceania: BothAustralia andNew Zealand have vast stretches of a kind of soil called, "loess " [English:loh-eus] , in which certain grape varieties develop a unique set of characteristics. These countries have gained much attention in recent years for some very fine white wines. In claiming that "its all in the dirt ", Australia and New Zealand are implying that they produce some of the best white wines found anywhere because of the characteristics of the regions' unique soil. Among Oceania's better known wine-growing regions are:

Barossa, McLaren Vale… (Australia )

Marlborough, Hawke’s Bay… (New Zealand )A thorough discussion about loess is available at Wikipedia.

South America :Chile andArgentina : have arisen over the horizon of classic winemakers. The high mountains of the northern regions produce both fine and value wines. Many of these wines may not be the very best, but are quite drinkable, despite being relatively inexpensive. Attention for this quality has focused on the dry, cool mountain weather, but attention has also focused on the region's soil, loess.Wind-blown loess is usually found inland of large bodies of water and imparts a unique character to the wines that are produced in these locales. Wine regions worth noting are:

Mendoza, Salta… (Argentina )

Elqui Valley, Maipo… (Chile )Storing Wine

Any bottle of decent wine should be stored properly. If not stored properly, wine can lose its complexity and palate or become contaminated with unwanted odors and flavors. To avoid spoilage, store wine in a cool place (

12–15 °C ;~52 °F ). Bear in mind, however, that other factors can also spoil wine in storage, especially low acidity.If one has a country house or lives in a rural area, storing wine two meters (about six feet) underground will assure a fairly constant temperature throughout the year. If not, one can rent storage space at a local restaurant or else store wine in a cabinet-style wine cellar (i.e. wine refrigerator). In Korea, one can store wine in a special compartment of a "gimchee refrigerator".

Wine Containers

Bottles: among a myriad of wine-bottle shapes and sizes, many bottle shapes have been named by their respective wine districts, though only a few shapes are prevalent.

Comparison of two popular wine bottles: notice the gentle curve of the Champagne bottle (left) versus the tall, slender shape of the Bordeaux bottle (right). The most popular shape worldwide is the so-called Bordeaux bottle that has a tall, cylindrical shape that curves sharply into a narrow neck. Because of the shape, bottles can be packed very densely during aging, storing, and shipping.

The second most popular bottle style is the Burgundy bottle, which has a vertical cylindrical base that curves more gently to a narrow neck than does the Bordeaux bottle. The gentle curves of the Burgundy bottle may lack the storage efficiency of the Bordeaux bottle, but they do have an air of elegance and aesthetic warmth.

Similar to the

Burgundy bottle is the strongerChampagne bottle (left), which accentuates the shape of the Burgundy bottle. Champagne bottles must be very strong to withstand the high gas pressure inside the bottle. We must realize that Champagne isfermented twice : first in avat and then in abottle . As Champagne ferments in a bottle, carbon dioxide gas is produced, from whence comes the sparkling bubbles. As fermentation continues, pressure in the bottle builds up. Consequently, Champagne, or sparkling wine if you prefer, must be contained in heavy, thick glass.During the early years of sparkling wine production, some bottles of aging Champagne would burst, because the bottles were not strong enough to withstand the high gas pressure inside the bottle. The monks who made the sparkling wine referred to such badly behaving bottles as "

devil wine ". Popular grape varieties used in the production of Champagne include: Pinot noir, Chardonnay, and Pinot Meunier.Another popular bottle shape is the Alsace/Mosel bottle, which is a slim, cylindrical bottle. These bottles are also known as "

Riesling bottles ", because they are popular for bottling Riesling wines. Historically, Alsace/Mosel bottles were named after famed Rhine River wine-producing regions of France and Germany.These bottles all share one characteristic, a standard

size . Astandard bottle of wine is750 milliliters , while asplit , ordemi , ishalf the volume of a standard bottle. Wine at weddings and other large festive gatherings may be served from amagnum ,1.5 liters , or adouble magnum ,3 liters . Champagne bottles are limited in size because standard glass bottles larger than a magnum may burst from the high gas pressure inside any bottle of sparkling wine. For a really big party, wine can be ordered by thecase , which contains12 (one dozen) 750-mililiter bottles.

Cask, barrel, carboy, keg, vat… After reading all about winemaking, one may ask, "What is the difference between a cask, a barrel, a tank, a carboy, and a keg? " The answer lies insize andshape :

Carboys are clear-glass jugs up to6 gallons (22.7 liters) used by some wineries for intermediate-term wine aging before final aging. Tiny residual particles of skins and other debris that must be removed before final bottling are called "lees ", which fall to the bottom of the clear-glass container and are easily visible in a clear-glass carboy.

Barrel: A container that has rounded sides, as in "barrel-shaped". Barrels are made of woud, usually oak, and are available in sizes ranging from15 gallons (55 liters) to60 gallons (225 liters) . A barrel is sometimes referred to as asmall cask .

An intriguing question is "Why do barrels have rounded sides, rather than straight, or flat, sides? " A flat-sided barrel would be difficult to turn right or left as a winemaker rolls a barrel from one place to another. Curving the sides of a barrel permits easy turning as the winemaker rolls the barrel forward.

Besides a hint of aesthetic value, the curved shape of a barrel is quite functional; rolling left or right is possible with rounded sides; flat-sided barrels cannot easily be turned left or right. Cask can be thought of as a "large barrel". Long-term aging of wine is often done in very large casks.

Tank is a generic word that could loosely apply to any of the containers listed here. In wine-making circles, however, a tank may be thought of as having straight sides, as opposed to "barrelled" sides. Winery tanks are available in almost any size, but tend to be very large and made of stainless steel.

The production of fine wines usually requires years of time. Large wooden vats, or large barrels laid on their sides, are traditional, long-term storage containers. Vat is a generic word for large tank, cask (Old French), or barrel (Latin).

Keg is a pressurized container that is usually associated with transporting and storing beer. Because beer iscarbonated (as is sparkling wine), beer must be stored and transported under pressure.Alcohol and Good Health

We all have suffered the consequences at one time or another of having had too much to drink, but

does drinking alcohol in moderation have health benefits? The answer much depends on which experts you cite.Negative views of alcohol consumption seem to be more readily accepted than positive views of alcohol. Yet, alcohol is popular.

What are some of the health benefits of alcohol that are claimed by "experts"? A quick scan of Internet talk uncovers various studies, which may or may not be valid, a circumstance that pleads for further, reliable scientific investigation in order to settle the issue. Suggested benefits of drinkingalcohol include:

- Raises levels of HDLs (good cholesterol)

- Reduces the incidence of cognitive impairment (Alzheimer's disease)

- Normalizes blood clotting (minimizes heart attacks and strokes)

- Elevates response to insulin (less medication needed)

- Lowers the probability of having diabetes

Several biological problems exist. First,

genetics plays a role in some cases of alcohol intolerance. Some humans cannot metabalize alcohol because of their genetic configuration. A percentage of the population is prone to alcohol addiction, which is a serious public safety issue.Another factor that clouds the issue of benefits is in the

use of the word alcohol .Is whisky better or worse for good health than wine or beer? An apple a day may keep the doctor away, but two glasses of red wine a day may also keep the doctor away. Some people may be less suseptible to intoxication by virtue of eating a diet high in B-vitamins, an effect that has been observed annecdotally.Many commentaries and studies revolve around two glasses of wine per day. Two is only a guess as to how much alcohol is, or might be, beneficial. More objective studies will almost certainly demonstrate that higher or lower levels of intake may be beneficial to different segments of the population.

An entire library of books would probably not settle this issue, so let this author just share an anecdotal observation or two.

Drinking wine with meals seems to help digestion, as well as enhancing the enjoyment of food. As a relaxant, a glass or two of wine may be a better anti-depressant than many prescription drugs. Let us not discount the value of "truth in wine" or the pleasure of sharing a spontaneous flow of ideas or sharing camaraderie with friends.

Low-quality spirits of any ilk, however, can lead to un-pleasantries, such as severe intoxication and next-day

hangovers . Let us add thattoo much of anything is not good , including excesses of food, vitamins, exercise, pure water, and other good things. Good things can be abused. "Nothing in excess " was inscribed at the ancient Greek temple of Apollo Delphi. In modern times, we may want to follow the advice of the ages and drink inmoderation .Closing

We hope that the foregoing discussion clears the air on an assortment of wine-related topics and has passed along enough enlightening information to warrant addressing you as at least an aspiring sommelier. The aim is to help you discover what you like in wine.

The Roman poet Horace considered wine an aphrodisiac and suggested that one should not drink much poor wine, but for fine wine, Horace said, "Pile high the hearth and bring out the old [i.e., well-aged] wine. Leave all else to the gods. (Horace, 65 BCE–27 BCE) From the Roman poetic archives, one might draw the conclusion that fine wine is indeed the"nectar of the gods "

Till we meet again,C h e e r s !

Guhn-bae (Korea)

Kahn-pah-i (Japan)

Gan bay (Mandaran)

Tchin tchin (China)

Chin chin (formal),Saluté (informal)(Italy)

Santé andA votre santé (France)

Salud (Spain)

Skaul (Scandinavia)

L'Chay-yim (Hebrew)

Prost (Informal) andZum wohl

Preferred when drinking wine(Germany)

For fun, take a short

Table of Contents

- In the Beginning

- An Enduring Beverage

- Fermentation

Alcohol or vinegar

Carbon dioxide

Ethyl alcohol and methyl alcohol

Acetic acid - Making Wine

- Selecting Wine

Maceration of the "must"

Color

Primary and secondary fermentation

Aging

Labels

Sparkling vs still wine - Characteristics of Fine Wine

Complexity

Tannins

Balance - Components of Complexity and Balance

Alcohol content

Acidity (pH )

Color

Nose (Aroma )

Palette (Taste )

Finish (After taste ) - Grape Varieties

- Terroir, the Land

- Grape-Growing Regions

Beaujolais, Chablis…(France)

Tuscany, Piedmont…(Italy)

Senoma County, Napa Valley…

(USA, California)

Rioja, Ribera del Duero…(Spain)

Rheingau, Pfalz…(Germany) - Storing Wine

- Wine Containers

Bottles

Barrels

Casks

Kegs

Carboys

Tanks

Vats - Alcohol and Good Health

- Closing

- Cheers

Merlot

Zinfandel

Tempranillo

Nebbiolo

Grenache

Malbec

Syrah [

Pinot Noir

Pinot Grigio

Muscat Blanc

Chardonnay

Barossa, McLaren Vale…

Mendoza, Salta…

Elqui Valley, Maipo…

Wine Quiz

To see the correct answer, move your mouse cursor over a slide. Moving the cursor away from the slide will restore the original, unanswered question (slides by Baldasare).

Quiz Question 1

Quiz Question 2

Quiz Question 3

Quiz Question 4

Quiz Question 5

Quiz Question 6

Quiz Question 7

Quiz Question 8

Quiz Question 9

Quiz Question 10

The End

If you answered all ten questions correctly, you are well on your way to appreciate fully a fine bottle of wine with a fine meal.

Return to Top of Wine Tutorial

Return to Top of Wine Quiz

Return to Home Page:

Window on the World